Show Me A Change Maker: Dr Marcella Ucci, Professor

Interview - Marcella Ucci

FP: So, tell us about your journey and what brought you to researching sustainable and healthy buildings?

MU: Originally I was an architect in Naples, Italy. Then towards the end of my undergraduate studies, I developed an interest in what was then known as bio-architecture. It’s not a common term, but it really kindled my interest and gave me a new focus. It was all about how we create buildings that support people while also being sustainable.

Next, I joined an exchange programme between the EU and the UK, which led to an Environmental Design Engineering Master’s at the Bartlett at University College London. I was then offered a contract as a research assistant and ended up in the world of academia doing PhD in indoor air quality.

My first job as a researcher was looking at a model that predicts how dust mite infestations might be affected by housing conditions, building design, etc. It was a very unusual job because we collaborated with the entomologist. We were talking about what we should feed the dust mites that were kept in the lab – to feed them a more ‘natural’ diet – I was taking the minutes of the meetings which included reminding senior colleagues to bring their beard shavings to the next meetings, to help feed the mites! You know, so it’s a very diverse job.

After the dust mites project and PhD, I accepted a lectureship at UCL in facility and environment management. It taught me the importance of operations in buildings, and the differences between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ FM. I later taught on the same master’s degree which I studied originally – Environmental Design and Engineering.

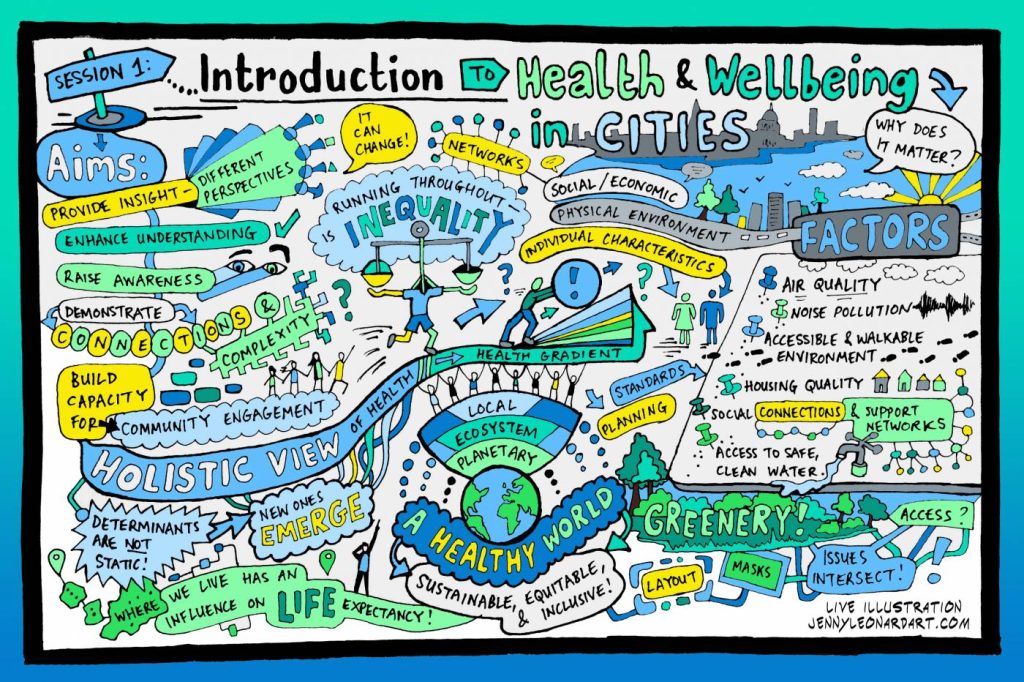

My research and teaching activities has always centred around my interest in sustainability, energy efficiency, health, and well-being. Health inequalities is a topic very close to my heart, sadly, in the UK, there are many inequalities, some of which are deeply embedded in the built environment.

FP: So why do you think interest in the link between sustainable practice and the built environment is growing?

MU: Climate change is a very good example of how environmental emergencies affect our lives deeply. Now we also see how the lack of sustainable fuel sources and dependency on sources which are polluting and controlled by few countries worldwide can impact our lives. So there is growing interest from younger generations. It shows how environmental degradation affects human health. When I did my MSc in Environmental Design Engineering, that was a very niche topic at the time, whereas now, it’s becoming a lot more mainstream.

FP: What would you say is your proudest project?

MU: I am extremely proud of having led the development and launch of the master’s degree Health Wellbeing and Sustainable Buildings course. The opportunity to educate the future leaders of the built environment is an invaluable one. I am delighted when I publish papers, but I’m equally delighted when I see where my students putting in practice what they learnt from the programme, with an aim to improving our world.

FP: Where do you look to for motivation?

MU: I look for motivation in making a difference within real-life contexts. There is often a perception that academics are in an “ivory tower”. For me, it’s quite the opposite. I am doing research and teaching topics that tackle the issues creating societal challenges. When I read about research and see an opportunity to tackle this problem, that is what I find motivating and inspiring. That and walking with my dog to decompress and think about things. Movement is so important.

FP: Since the public has become more aware of buildings’ impacts, how has the industry developed?

MU: When I first did my MSc, it focused on passive design strategies. Rather than the supply side of energy or renewables. The perception was that we could and should try and reduce demand – ideally through a technological solution.

An understanding then developed that technological solutions don’t always work. We also must understand the social-technical environment, behavioural independence, implications etc. And now there’s the idea – let’s reduce energy, let’s reduce carbon – which is sometimes at the expense of health and well-being.

The epiphany moment came when the World Green Building Council published the report on office well-being. The report tried to change the dialogue by saying – sell green buildings because they also make people healthier; people are the most expensive corporate asset. This is a renaissance of our health and well-being.

FP: So, what challenges does the industry face?

MU: The industry is very scattered; some are engaged with the zero-carbon agenda, others talk about health, well-being, climate change, etc. I was asked recently, “Well, should we save energy? Should we prioritise energy saving above health and well-being in buildings? How do you decide whether to prioritise one or the other?”

Of course, this is both an ethical and practical question. The important thing at the moment is ensuring that the most disadvantaged people are not the ones left behind in the intersection between the energy, climate change, health, and well-being agendas. Unfortunately, if we only leverage via the market, there is a significant risk that this will happen.

FP: From that perspective, where do you think there’s potential for positive change, within awareness of health or awareness of actually building sustainably?

MU: One sector seeing real growth is indoor air quality. It was somewhat ignored for a long time; researchers in the field were frustrated that they were almost the “Cinderella” within the world of sustainable practice, never invited to the ball. I was a member of the Working Group which produced the report from the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health on the impacts of indoor air quality on children and young people. It showed that the risks to health arising from poor indoor air quality must be taken seriously – several recommendations were put forward and indeed this is now a very active research field.

People are becoming more aware that indoor air quality can affect their health just as much as outdoor air pollution. It is an excellent opportunity to rekindle industry interest in ventilation and connect it to materials used and their effects. How do we inform the general public about indoor air quality risks without creating distrust? What are the right tools?

FP: You’re working with other academics working with other researchers, you’ve got students. How do you motivate people?

MU: Most people I work with have an inquiring mind and love a challenge, in terms of “Okay, we don’t know this problem. We don’t know how to solve this problem. Let’s try and figure it out.” That in itself is motivating. Of course, we try and focus on things that might get the best return in terms of effects, but in this industry, we are also very motivated by making a difference – a difference on individuals and society.

Something that I always try to do with my students is understand what they are trying to achieve and what motivates them. Then I try to ensure that their MSc or PhD dissertation, or whatever else, is based on those foundations. To have a mutual understanding of what we are trying to achieve. Sometimes the failure of a project results from not sufficiently listening to each other and understanding each other’s perspectives, needs, expectations, desires and dreams. We take that for granted that I know what you’re doing, and I know what you know, but it’s rarely the case. Building a commonly shared understanding of the problem is key to identifying successful solutions, especially in interdisciplinary projects.

FP: I guess every individual has different motivations for their actions, for example in an orchestra everyone’s playing a slightly different instrument to create a symphony.

MU: Exactly, and I mean, I work in multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary teams, and that’s one of the biggest challenges and opportunities. You need to understand each other’s perspectives to work together towards a shared common goal. And it takes time to get those perspectives understood mutually. Sometimes you realise – we’re not working towards the same goal, are we? But even then, what is it that we can carve, that we, you know, we can do together?

FP: How did you come to find out about FirstPlanIt and our work for sustainable construction?

MU: Ankita is a graduate of the MSc that I mentioned and talked to me early on in the conception of FirstPlanIt, while still a student. Ankita was selected for a specialised programme that fostered innovation. We would talk about all these exciting ideas. That’s how I became acquainted with the project and its work within sustainability. Digital solutions hold an important place in helping create positive change. We know that digital tools can help a lot in many different ways. There is a lot of interest in these tools. So it’s a no brainer, if it’s done properly.